Dual Process Theories Bundle Too Much

(The gaps between posts are getting shorter! Surely this trend will continue until my posting output overwhelms the capacity of the entire internet, crashes it, and ushers us into a new age of low-tech cyber punk apocalypse!

I know the last post left the promise of a sequel. This post is not the sequel, though it also promises a sequel! In general, don’t expect the chronologically next post the be a sequel. Topics will be looped through until it makes sense to return.)

The Hidden and Biased Brain

As a teenager I went on a multi-year pop-psychology reading binge. My best estimate puts it somewhere between 12 and 30 books that all seemed to be talking about the same thing. To describe by pointing, here’s a sample of titles and their taglines:

Compelling People: The hidden qualities that make us influential

Future Babble: Why pundits are hedgehogs and foxes know best

Blink: The power of thinking without thinking

Predictably Irrational: The hidden forces that shape our decisions

What Every Body Is Saying: An Ex-FBI Agent’s guide to speed-reading people

Freakenomics: A rogue economist explores the hidden side of everything

Fooled By Randomness: The hidden role of chance in life

Subliminal: How your unconscious mind rules your behavior

Coercion: Why we listen to what “they” say

And perhaps a bit on the nose:

You Are Not So Smart: Why you have too many friends on facebook, why your memory is mostly fiction, and 46 other ways you’re deluding yourself.

I’ve got mixed feelings about this cluster of books. On the one hand, it fed and nourished my early curiosity about the mind. On the other hand… a huge amount of it is wrong. Either wrong as in the studies simply do not replicate, or wrong in the sense that some interesting studies are used to prop up generalizations about human behavior that are far grander the evidence warrants. I’m going to explore a specific problem I have with the cluster, but first we need to learn more about the cluster as a whole.

The unifying pillars of this cluster are the “hidden” brain and the “biased” brain, the respective ideas that people don’t actually know what’s going on in their minds, and that what’s going on is largely biased ad-hoc heuristics. The Elephant in the Brain by Robin Hanson and Kevin Simler is the most refined version of the hidden brain thesis. Most books fail to address why we have “hidden parts of our minds”, and why self-deception would even be a thing in the first place. It largely pulls from Robert Trivers’ view on self-deception, that we “deceive ourselves so we can better deceive others”.

Thinking, Fast and Slow by Daniel Kahneman is the most refined version of the biased brain thesis. That has something to do with the fact that Kahneman co-founded the entire academic field that gave rise to all of these pop-psychology books in the first place. Back in the 70’s, he and Amos Tversky kicked off the Heuristics and Biases research program. Since I came of age in a world that already had Kahneman and Tversky deep in the water supply, it was useful to get a picture for what the academic scene was like before them. From Thinking, Fast and Slow:

“Social scientists in the 1970s broadly accepted two ideas about human nature. First, people are generally rational, and their thinking is normally sound. Second, emotions such as fear, affection, and hatred explain most of the occasions on which people depart from rationality. Our article challenged both assumptions without discussing them directly. We documented systematic errors in the thinking of normal people, and we traced these errors to the design of the machinery of cognition rather than to the corruption of thought by emotion.”

Apparently, there really was a time where academics treated everyone as “rational agents”, where “rational” means an ad-hoc mashup of a mathematical abstraction (VNM axioms of rationality) and a poorly examined set of assumptions of what people care about. Well, I mean, people still do that. The real difference now is that if you disagree with them you have a prestigious camp of academics on your side, instead of feeling like a lone voice in the wilderness.

(As an aside, I’m not going to put much effort into appreciating the intellectual progress that the Biased Brain and Hidden Brain thesis represent before going into the critique. This is mostly because I grew up with them and the world that came before them is only partially real to me. In my emotional landscape, they are the establishment, so that’s what I’ve gotta speak to.)

So what’s my beef? Where do things go wrong?

As I previously mentioned, there's a shit ton of psychology that simply doesn't replicate. Kahneman makes heavy reference to priming research and ego depletion research, neither of which has anything going for it.

Writers and researchers in this cluster also have the problem of defending their concepts of bias. A bias is a deviation from something, supposedly something that you intended and wanted. In order to talk about bias, there must be a reference point of what unbiased would mean. I’m not the sort of relativist that thinks this is impossible — it's not. My problem here is that no one I’ve read on the topic of biases has put in much, if any, effort into outlining a specific stance and defending it. It’s often assumed that we’re all on the same side in regards to what counts as bias.

If you want an extensive academic critique of Kahneman-style heuristics and biased research, check out Gigerenzer.

To understand my beef, we need to look more closely at the ways that some of the biased brain books split the mind into parts.

Dual Process Theories

Kahneman's book introduces a framework of two systems to understand human behavior. More or less, the takeaway is that System 1 is fast, biased, and unconscious, while System 2 is slow, rational, and conscious. From the man himself:

“System 1 operates automatically and quickly, with little or no effort and no sense of voluntary control. System 2 allocates attention to the effortful mental activities that demand it, including complex computations. The operations of System 2 are often associated with the subjective experience of agency, choice, and concentration.”

Splitting the mind into two such parts is by no means unique to Kahneman. Kahneman’s is just a specific instantiation of a dual process theory, which has been getting more and more popular the past half-century. Kaj Sotala (whose writing was my original inspiration for this post) expands on this:

“The terms System 1 and System 2 were originally coined by the psychologist Keith Stanovich and then popularized by Daniel Kahneman in his book Thinking, Fast and Slow. Stanovich noted that a number of fields within psychology had been developing various kinds of theories distinguishing between fast/intuitive on the one hand and slow/deliberative thinking on the other. Often these fields were not aware of each other. The S1/S2 model was offered as a general version of these specific theories, highlighting features of the two modes of thought that tended to appear in all the theories.”

What these models have in common is that they carve the mind into two processes, one that is intentional, controllable, conscious, and effortful, and another that is unintentional, uncontrollable, unconscious, and efficient. This “bundling” together of properties is the defining feature of a dual process theory, and it’s where everything goes horribly wrong.

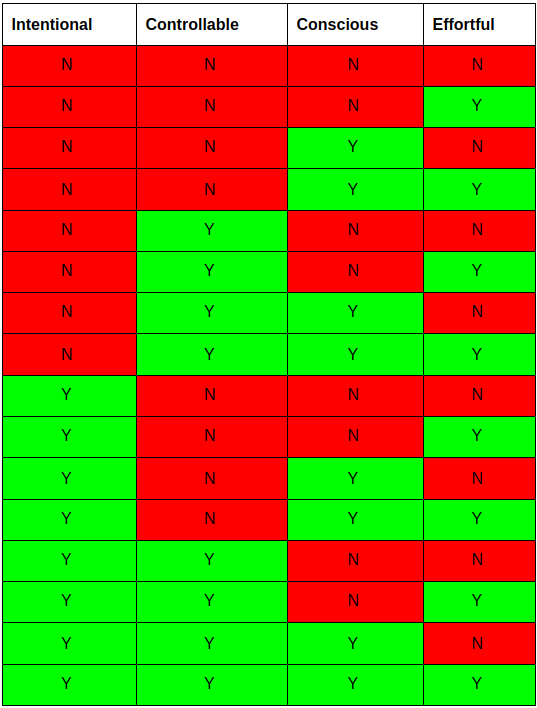

The argument is pretty straightforward. Suppose you have four properties that a mental process could have. To simplify, we’ll imagine each property as quite binary, either it’s intentional, or it’s not intentional (this isn’t true, and the gradations of intentionality, consciousness, and effort are incredibly interesting and could be a whole other post). There are 16 different ways you could group together these properties. If you don’t see where the 16 came from, this table should visually explain it:

Dual process theories start with the idea that the only possible combinations are the very first and very last ones. That you aren’t going to have any intentional, uncontrollable, unconscious, effortful thought. Or if not impossible, the idea of a dual process theory is that these two combinations are the most likely to occur, and all the others are rare or insignificant enough to be negligible. If this is not the case, if these properties don’t come all bundled together, then the dual process split fundamentally doesn’t make sense as two categories. The Mythical Number Two, a paper that explores issues with dual process theories, gives an excellent analogy:

“Consider this analogy: we say that there are two types of cars, convertibles and hard-tops. No debate there. But now we say: there are two types of cars, automatic and manual transmission. Yes, those are certainly two different types of cars. And still further: there are two types of cars, gasoline and electric motors. Or: foreign and domestic. The point is that all of these are different types of cars. But we all know that there are not just two types of cars overall: convertibles that all have manual transmission, gasoline engines, and are manufactured overseas; and hard-tops that all have automatic transmission, electric engines, and are made in our own country. All around us we see counterexamples, automobiles that are some other combination of these basic features.”

Unless you see all of the relevant dimensions align together into the clusters you want, there’s not much of a basis for saying “these are the two types of thinking, System 1 and System 2”. You’ve just arbitrarily picked two subsets and made them your entire world.

To seal the deal, we need a bunch of concrete counterexamples to the typical dual process bundling. I’m going to save that for a follow up post, though I’m sure you could come up with some yourself if you brainstormed for 5 minutes. Additionally, you could read the paper I just quoted.

Bundling Drives and Cognitive Ability

The last section was looking at the “steel man”: the dual process theories that are actually proposed by researchers in academic settings who read the literature and do experiments and are handsome and praiseworthy and charming and…

Given that the popular version always looks different from the source, and the source was already on pretty shaky ground, you can guess that I’ve got even more beef with popular dual process theories of the mind.

The cluster of books I’ve been pointing to all paint a very similar picture. Tim Urban at WaitButWhy gives the clearest illustration of such a model, one that I think is fairly exemplary of this space, and 100% exemplary of how I used to think. He coins two characters: the Primitive Mind and the Higher Mind.

They’re each in control of one side of this dashboard

As you might expect, the Primitive Mind isn’t that smart, can’t really think ahead, and is focused on just staying alive. It thinks in quick zigs and zags of intuition. The Higher Mind is where all of human intelligence happens. It thinks with thought out reason. Along with the functional split, there’s a historical split. The Primitive Mind is the older part of the brain, ancient software written by the blind hand of evolution. It’s shared by many other animals and it is the base survival-oriented part of us. The Higher Mind is a more recent development.

To hear a very similar story, though with less fun drawing, watch this interview with Elon Musk up til the 1:20 mark

“A monkey brain with a computer on top.”

“Most of our impulses come from the monkey brain.”

“Surely it seems like the really smart thing should control the dumb thing, but normally the dumb thing controls the smart thing.”

Even though Urban makes no reference to brain anatomy, and Musk specifically connects his frame to regions of the brain (limbic system, neocortex), I think they’re more or less working with the same mental mode. In this Urban-Musk model (which yes, that is in fact a perfume), an even more dramatic bundling occurs. Not only are intentionality, controllability, consciousness, and effort all bundled together, but so are the dimensions of:

The capacity to get correct answers

Drives, from impulses to values

Identity and who you are.

We’ll briefly look at each of these, and I’ll state the points I want to make without really backing them up.

Capacity to get correct answers:

This is pretty straightforward, and also present in academic dual process theories. It’s the idea that one system is biased and the other is rational. The pop version dials it up, where biased becomes generally “stupid” and rational becomes “intelligent”. I use quotes for each, because I get the sense that a lot of people don’t distinguish between “producing outcomes they like” and “accurately modeling and steering the world”. They’ll blend the notion of stupid into “doing things I don’t like” and smart into “doing things I like”. When people do piece them apart, there’s a general sentiment that your Primitive Mind (often framed as your intuition or your gut) will get a question wrong more often than your Higher Mind (often framed as your reason).

Eventually I’m going to argue that your intuition is as good as the data it’s trained on, and your reasoning is as good as the systems of reasoning that you practice. The normative correctness of intuition vs reason is not a factor of innate capabilities of certain mental subsystems, but a result of the quality of your learning.

Drives, from impulses to values:

I expect most people to associate “impulses” with all those dials on the Primitive Mind’s side of the control panel (“I’m hungry” “I’m horny” “I’m jealous”). They might use language like, “your Primitive Mind governs your impulses and your Higher Mind governs your values”. I’m going to use drives as a more general term to value-neutrally talk about things that... well... drive you. Musk and Urban explicitly claim that one system is responsible for what might be commonly called your base or vulgar drives, and that the other is responsible for the drives that are often called good or prosocial. Additionally, these two clusters are frequently in conflict.

While I do think it’s the case that many people have constant conflict between competing drives, I don’t think those drives cluster into groups that align with any of the other properties the Higher Mind and Primitive Mind bundle together. You can scheme intelligently to get food, and you can stupidly follow your curiosity off a cliff. You can be unconscious of your noble desire to contribute to a shared good, and you can be acutely aware of your desire to have sex. Furthermore, drives within the Primitive Mind can and do war with each other all the time, as do drives within the Higher Mind. Any drive can war with any other drive depending on the circumstances. I find it significantly more clarifying to think about the general dynamics of conflict between drives, instead of the narrow-minded conflicts between the Primitive and Higher minds.

Identity and who you are:

This last one is probably the sneakiest and most complicated, because there’s so little shared language to talk about the self, the ego, self-concept, conscious awareness, the process of identification, etc. As Urban and Musk tell it, the Higher Mind/neocortex is what makes us human. Not only is it what makes us human, it’s literally you. When you do the thing we call “consciously thinking about something”, that’s supposed to be the Higher Mind. The primitive mind is other, a thing that gets in the way of your plans. You have to play nice to the degree that it can’t be surgically removed, but other than that, it’s a direct conflict of you trying to control it. Kahneman even alludes to this in his first description of System 2, saying “The operations of System 2 are often associated with the subjective experience of agency, choice, and concentration.”

This is the point I’ll be least able to make sense in a short amount of space, so I’m just going to give this possible cryptic paragraph and hope it lands: I’m working towards showing that S1/S2 isn’t a coherent category split. Neither is the Higher Mind and the Primitive Mind. They both declare this division, and assume each side has a monopoly on all these other qualities. Given that they don’t, and there’s no coherent truth to the Primitive Mind or the Higher mind, when I identify with the Higher Mind, what am I actually identifying with? I think what’s happening is I have a self-concept that utilizes the qualities described in the Higher Mind, and this self-concept is exerting authoritarian control over me-in-my-entirety. This hurts me in the short run and the long run, and is really important to address.

What You Miss When You Bundle

All this bundling gets in the way of thinking because it blurs important distinctions and pushes you to infer connections that might not exist. Let’s take a single aspect of this bundling; that the biased parts of your mind line up with the unconscious parts of your mind. Back to The Mythical Number Two for an example:

“For instance, the first research on implicit bias (i.e., the unintentional activation of racially biased attitudes) occurred in 1995 64, and by 1999 researchers started referring to this phenomenon as unconscious bias 65. Soon enough, people around the world learned that implicit biases are unavailable to introspection. Yet conscious awareness of implicit bias was not assessed until 2014, when it was found that people are aware of their implicit biases after all 66.”

That’s wild to me, because I see the claim that people aren’t aware of their biases as a load bearing aspect of the narrative around implicit bias that has become mainstream in the past two decades. This narrative got big because it seemed like a way to push people to change without making them feel like they were being called Bad People (and then resisting change). This seemed plausible because a common moral sentiment is that you aren’t blameworthy for something that you aren’t aware you’re doing. It seemed plausible that people could stomach “okay, I’m reinforcing bad shit in the world because I’m biased, but the bias is unconscious, and also everyone else is biased, so I’m not personally super blame-worthy and I’m not going to be attacked.” This whole narrative falls apart if bias and the unconscious aren’t bundled together.

I eventually want to be able to talk about how our systems of punishment work, at the group and the state level. I want to talk about people's mental models of justice, blame and punishment. A lot of our moral reasoning makes heavy use of concepts like intentionality and conscious awareness, and I don’t want to try and investigate this topic from an intellectual framework (dual process theories) that obscures how intentionality and consciousness work and interrelate.

Unbundling can help us understand other things as well. Remember those Hidden Brain books, the one’s telling us about how we’ve got all these hidden motives, how no one can introspect, and how everyone’s reasons are fake? None of them give any insight into piecing apart the confabulations from The Real McCoy. It’s obvious that I know why I’m doing things sometimes. And I certainly don’t know why I’m doing things plenty of the time. And I’ve observed my own ability to spin stories and provide false reasons for my behavior. What’s the difference that makes the difference? To have any hope of answering this, we’ve got to undo the bundling that comes with dual process theories and try to understand how introspection, self-awareness, and intentionality actually work.

I’ve spent a lot of time talking about how I think the mind doesn’t work and not much time talking about how I think it does work. A crucial part of writing for me is communicating the motivations that make me care about a topic in the first place. Hopefully you have a sense of where I’m coming from, and why dual process theories of the mind feel so unsatisfying and unhelpful to me.

Things to talk about next:

Build up some vocab and clarify terms to talk more precisely about the mind.

Go through a ton of examples where dual process bundling fails.

If S1/S2 isn't a real split in the mind, why did I spend several years feeling like it was so right and like it explained so much? What other features of the mind was I implicitly tracking when I was using S1/S2?

Thanks for reading!

Stay Lucky,

Hazard

Increasingly convinced that the missing piece is language, which is what the computer is made of and which the monkey brain can't understand and occasionally hates. I think of the mind as an oil slick on an ocean: that slick is language. To extend the metaphor, anyone looking at this mostly sees the slick, since it grabs attention. If you engage with the slick, you immediately get covered in slick, not ocean water. But there's a lot going on underneath.

Many convincing modern approaches to therapy seem to be working with this dichotomy, even if they don't engage it directly. I'm thinking of Gensler and even "brain retraining" efforts like EMDR.

Very interesting article.

You talk both about popular psychology as well as more scientific research.

For pop-psychology there are some aspects that you don't touch on:

(1) They exist in a specific cultural context.

(2) The measure for popularity is probably both "entertainment" as well as if people find them helpful.

From the reading list and that you read them as a teenager, I assume you were born sometime in the 90s. I'm probably ~10 years older and remember vividly reading Blink and later the books by Dan Ariely. All of them were in some way eye-opening. I found that they touched on things that were not spelled out very explicitly in education or popular culture much before that. I found these concepts very helpful to grasp my mind, thinking and behavior better. For that to be the case, the books neither need to be correct or paint a fully nuanced picture. Even if the model is wrong, it may be helpful for me to change my behavior or feel better.

I could imagine coming across these concepts earlier, and the concepts being more widely spread in popular culture, makes it more obvious where they fall flat and lack nuance. I think pop-psychology/self-help books can go through cycles. Initially they are helpful, introducing concepts that remove limiting beliefs. Later on, they may actually be creating limiting beliefs themselves, as common understanding changes. I see some things that were presented in popular culture during my childhood that way: They were probably well intended and helped people earlier, but were very counter-productive for me and I had to free myself from these concepts.

I love the more nuanced view you present here, including the critique of these concepts!